[ 10 min] Curt –

The Course and Conduct of a Revolution orCivil War

“Understanding the Dynamics of Revolution and Civil War: Causes, Methods, and the U.S. Context”

- Setting Up the Context

- The Present Condition

- How We Got Here

- The Cause of Revolution and Civil War

- The Emergence of an Age of Discord(Crisis)

- Means of Revolution and Civil War

- Possible Means of US Conflict

- Possibilities of Revolution, Civil War or Collapse

- The Solution

- The Choice

Set Up The Context.

- I’m Curt Doolittle (brief Background)

- Note for all, book and this presentation to tie back to question of moritz.

- First, an apology. I have done myself, the work, you, and our movement a bit of a disservice. (libertarian, then, association with the hard right, when while our reasoning is conservative – meaning empirical – our solutions are classical liberal to libertarian: a continuation of the germanic > anglo > American tradition of a high trust polity.

- I’m going to try to correct disservice, because we need to correct it.

- We decided over a year ago that we were done with research and development and that it was time to go to market with these conferences, our videos, and very shortly our first book – our first volume in the series.

- We are the culmination of and very likely, something close to the end point of the work from aristotle to aquinas to anglo-scottish enlightenment, to the founders to those great minds of the early 20th who unfortunately failed to counter the Marxist-to woke sequence of pseudoscience, sophistry, fraud, and deceit,

- In historical context, we are as important behavioral science as was darwin in biology. We are the anti-marx, anti-feminine, anti-left, restorers of the western group evolutionary strategy, and it’s spectrum of institutions.

- And we are beginning to see the present age as equal to and a repetition of the Axial age which gave birth to our european and asian philosophical, and south eurasian theological traditions. We cannot go backward – we’ve done that once and created a dark age of ignorance. Instead, we must go forward finding a new means of organizing people at present scales with present economies, technologies, and knowledge of the universe.

- Who are we talking to given that the right is anti-intellectual, and while the libertarians had held the torch for conservative intellectualism, they have crashed and burned on the naivety of their pretense of the nature of man.

- We are, as far as I know, the only conservative and classical liberal intellectuals working today, using any semblance of science as our foundations.

- Why are we really here?

- … Our First conference: introducing ourselves, the science of western civ, and the scope of our solutions.

- … Our Second conference: identifying the enemy, it’s cause, and our failure to suppress it.

- … This is our Third conference … where we take off the mask and explain how to defeat the enemy and it’s strategy – forever.

- So,

- What I hope to show you is a path to victory – possibly the only path to victory – and the impediments to it.

We’re The Engineers. But you need many leaders, and many participants.

Anyone, any leader, or any group, or any combinations of groups, can use our work to bring about a revolution, a reformation, and a restoration of civilization – saving it from an other of authoritarianism, collapse, and dark age.

Our Self-Understanding

In our minds, our mission, is the production of a solution to the crisis of the age, and the creation of an inquisition to prosecute the enemy out of capacity for evil.

What Do I Want To Get Across To You Today?

The Simple Version

Behavioral Economics

- Human beings seek to acquire.

- Human beings do not want to learn a new way to acquire

- Human opportunities become exhausted in a market for opportunities.

- Human expectations exceed the the capacity of the marketplace of opportunities to provide the value expected by the humans.

- Humans unfortunately double down on previous behavior rather than adapt to new opportunities behavior.

- As humans become stressed they will lower their tolerance for irreciprocity (proportionality) and will react rationally: ‘why don’t I kill you and take your stuff’.

- The marketplace is a social expression of networks of cooperation, which generates the social phenom which results in demand for ages of reorganization (discord, crisis, change).

- This is an eternal process unless the polity and society are organized for the continuous discovery of new opportunities which prevent the cycle of discord, crisis, and change)

The Reframing

- People believe history is a natural progression (whig history) or the progressive vision of history.

- History consists of a market that can be manipulated by those who have accumulated the capacity to coerce at scale by verbal (talking classes), remunerative(financial and economic), or force (state, bureaucracy) for good or ill.

- In every civilization the spectrum of elites serve their self interest at the expense of the population by claims of false promise and plausible deniability.

- And our institutions are insufficiently defensive against those despite the efforts of our anglo and american forefathers attempts to prevent the commercial, state, and church interests at the expense of the people.

- We are asking you to reframe your understanding of the world from political or moral bias, theology, philosophy, and ideology biases, into simple terms of it’s irreciprocal and immoral, amoral: Criminal, and reciprocal and moral: virtuous. In other words there is only criminality and non-criminality. It’s not an opinion. It’s not a philosophy or ideology. It’s just a incontestable science of decidability regardless of knowledge, bias, or opinion. Because the opposite is just criminality and war.

A System of Measurement

- As an organization we are introducing the system of measurement, decidability, and accountability that extends the suppression of simple and direct criminality to sophistical and indirect criminality at national and international scales so that we limit ourselves to non-coercive cooperative means.

- You might think this was impossible. That preventing the three classes of elites from manipulation, seduction, false promise, baiting into hazard, corruption, parasitism, sedition, and treason., But it turns ot it’s not. It’s just another incremental increase in the precision of measurement and decidability we call the natural, common, concurrent law of cooperation.

The Challenges We Face,

( … )

A Means of Success

( … )

The Choice

( … )

[60min] (tentative)

Outline:

- The Convergence

- What made the west unique and WEIRD…

- ( … )

- Every time we raise a class into agency….

- Lag: Resistance to adaptation into conformity with the class above

- Class = capacity to bear responsibility NOT income.

- Economic Lead

- Legal Lag

- Institutional Lag

- The utility and disutility of common law and concurrent legislation vs monarchy or authoritarianism in correcting these lags

- Global Lag as the world has caught up economically

- Lag: Resistance to adaptation into conformity with the class above

- The replacement of meritocracy with credentialism and the managerial state

- The overproduction of pseudo-elites and the resulting conflict and calcification of politics, economics, society, and geo strategy.

- The introduction of a hostile elite using the feminine-semitic method of warfare from within.

- The nature of women and our failure to suppress female antisocial behavior.

- The swarming of our numbers by immigrants to compensate for the introduction of women and the offset in reproduction.

- The oversupply of labor by the combination of women, immigrants, outsourcing.

- The resulting inequality of returns and as such of income.

- The resulting financial distress of increasing segments of the population.

- The resulting social distress as demands for conformity to reciprocity cross the border of ‘proportionality’ into disproportionality creating social conflict.

- The resulting decline in social cohesion and a rise in individualism and factionalism contribute to a breakdown as communal ‘trust, grace, tolerance’ weaken, society becomes more prone to conflict.

- The resulting weakening of state institutions, as trust in these institutions erodes, whether through corruption, inefficiency, or inability to enforce laws fairly, also leads to social breakdown.

- The resulting incentive of factions in the population to resort to non-institutional means of achieving their goals, including protests and revolutions.

- The resulting fiscal distress of the government as its false promises are falsified

- The resulting destruction of the family as the first institution of production – of generations that persist the group evolutionary strategy and its contents.

- The resulting destruction of socialization and adaptation as the second institution.

- The resulting destruction of economic competitiveness.

- The resulting destruction of strategic competitiveness.

- Leaving our legal system and our currency as the only strategic advantage … until they destroy that too.

- What made the west unique and WEIRD…

The Present Condition (state of Things)

- (macro) Determinism

- The destruction by false promise and demoralization

- the fomenting of conflict.

- the fomenting of conflict.

- Things Aren’t Good

- “lives Are Pretty Hard.” “victorian Work Conditions”

- Standard of Living Has Dropped, with Hand-To-Mouth, Minor Crises Driving Them Over the Edge.

- For the Young Generation, as Useless as They Are, Uneducated and Indoctrinated, They Are ‘screwed’.

- The nationalization and globalization of status and identity markets (self regulatory, competition, context)

- The Spiritual State of The West.

- Social Media just made us AWARE of the damage becuse we could circumvent the academy, media, state ‘cathedral’ complex.

- psychological

- biological

- social, economic, political

- the demand for mindfulness provided by the ability to ‘calculate’ one’s actions to produces successes reinforced by social proof (feedback)

- We are not aware (Sources of Our Confusion)

- of our ‘mindfulness’ needs (confidence, anti-neuroticism),

- nor are we aware of the importance of limited variation in the polity’s ‘system of weights and measures’.

- Nor are we aware of the importance of variation of those weights and measures from our group strategy.

- Nor are we aware of our group strategy’s variation from the laws of nature including the natural law.

- We only experience stress instead. (Therefore our work to make these things explicit.)

- (Brad’s Summary) … (tie to measurement)

( … )

- The destruction by false promise and demoralization

The Problem of Prediction of Means of Change and Outcomes from it

- The feminine means of warfare by the enemy is MORE destructive than the masculine means of warfare. Capital can be reconstructed. Children can be born. But destroy the information system of the polity and as the middle east shows, you cannot reconstruct the polity. Yet the only solution to the feminine means of warfare is the application of organized violence to suppress it, just as we suppress all means of warfare. The question is why westerners so oddly, alone among peoples of the earth, resist use of violence against the feminine means of warfare? (Sovereignty, reciprocity – we are our own vulnerability.)

- Each Generation Is Stuck in The Zeitgeist of Their Formative Years, so is Each Civilization. THis generation Are Stuck in The Mentality of 2005. So we have the problem not only of generations but of factions, because the enemy has been so successful at fomenting conflict as a means of generating demand for their authoritarianism.

- Frog in the boiling pot: “Nobody Sees It Coming, but it always happens” – the Determinism of Cw2

- The Difficulty in Predicting (despite Being Good at It)

- Determinism of Conflict

- Indeterminism of Means (field of Possibilities)

- The Problem Is Timing

- The Solution is to Take Control of Causality to Produce Determinism in Outcome

- And that is what we are up to at the Institute.

- How We Got Here

- How The Population Incorrectly Frames The Issue

- But The Real Cause of Failure Is ….

- How The Intellectual Class Frames The Crisis

- The Feminine Means of War

- Reasons for The Emergence of Conflict

- The Resulting Asymmetry of Power

- Asymmetry of Power Between the Left and the Right

- Present Asymmetry of Power Use in America

- Power and Asymmetry in the Triangle Model

- Decidability through Reciprocity

- Conclusion: Asymmetry and the Pursuit of Power

- Historical Context: Evolution of Power Dynamics in the U.S.

- The Right’s Balanced Approach

- Social Psychology of Power and Responsibility

- Institutional Outcomes of Power Asymmetry

- Refined Analysis: Asymmetry of Power in Subsidy and Responsibility

How We Got Here

The present (third) age of expansion. History: (

- Ages:

- 1 – Feudalism: Early Middle Ages to the Late Middle Ages (roughly 9th century to the 15th century)

- 2 – Chivalry: High Middle Ages (roughly 11th century to the 15th century)

- 3 – Commercial Capitalism: Late Middle Ages to Early Modern Period (roughly 14th century to the 18th century)

- 4 – Monopoly Capitalism: Industrial Revolution to the 20th century (roughly late 18th century to the early 20th century)

- Start of the Age of Recovery 1200 – Restoration of the classical works from the middle east, the restoration of trade by the Hanseatic League, the formation of the free cities, the reformation of crhistianity by Aquinas and the Scholastics.

- The First Wave – The Restoration of European Self Determination (Renaissance) 1300+

- The Second Wave: – The Fall of Constantinople 1453 forcing the age of sail.

- The printing press and mass production of knowledge 1440

- The Thirds Wave of Reason – The Reformation

- The The first scientific revolution 1600s

- The invention of crucible steel in britain in 1740

- Start of The Age of Expansion: ~1730 – 1830,

- Industrial revolution: 1750-1900 (the cricket in 1776)

- Was made possible by financial capitalism and the rule of law necessary for the the development of stock corporations – which became ossified in monopoly capitalism.

- Aristocracy caves: 1830-1885

- Marx and Company 1847 (Labor)

- The theory of the leisure class emergence 1899 (Upper middle)

- destroying the empire by monopoly capitalism by 1914 (war);

- The shift from moral to economic decidability (measurement) in government.

- The shift of aristocracy and nationalism by the rise of financialism and globalism and unfortunately mass democracy instead of responsible democracy. (british empire and colonialism)

- The success of the upper middle class (finance, industry, media) in replacing the aristocracy (military, political)

- The progressive ambition of the managerial state (technocracy) 1910 – 1930s (Colonel Edward M House – Describing it (1912); Burnham: The Machiavellians 1942);

- The Financial Sector, The Corporations, and the Capture of the State by financial sectors. (Recognition of Rothschild 1885, by Queen Victoria) (concentration camps in south africa in 1900)

- The utility of finance in the capture and settlement of the american continent and the british empire in particular.

- 1950s – The mantle to the american empire (from the center of the civ (england) to the periphery (usa and the west) 1900-1945;

- 1930s – The postwar migration of jewish-german marxists to the USA converting labor marxism to cultural then race marxism (leninism).

- 1950s-60s – Fomenting Conflict: The Capture of Progressivism (positive, christian) by the Marxist Sequence (negative, jewish) ; T

NET RESULT

- Industrial revolution: 1750-1900 (the cricket in 1776)

- A problem of measurement (failure of accounting) – baiting into hazard. A failure of full accounting.

3) The Age of Discord, Conflict, an Collapse

- The Hostile (Criminal Elites) Made Possible By This Shift

- The Destruction of the British Empire by Financial Elites and the movement of financial elites to the USA. (They can’t tolerate productivity competing with financial parasitism.)

- ….

- Power via Money and The Vote: The Progressive (positive christian caretaking) vs Marxist (negative and atheistic and materialistic jewish) Revolutions

- The Introduction of Women (Irresponsibility)

- Women voters rapidly moved from responsible to irresponsible voters NOTE (because that is the origin of sex differences.)

- Them anagerial revolution: In talking classes, in industry and Government.

- Traditional capitalist entrepreneurs are being replaced by a new class of professional managers – (imitating the soviets)

- The credentialist revolution, (defeating meritocracy Military, nobility, industry) in government

- The capture of talking classes (church) Academy, Education, Media, Entertainment in the private sector

- Contrary to Burnham it was and remains the financial sector that holds power, not the corporations nor the state.

- New Monopoly outside the Market: (substitution for the church) The collapse of the division of labor between the church (familial and local social administration) and the Aristocracy (economic, political, and strategic administration) which was a marketplace, and their capture by managerial government and education both of which feed their constituency (financial, media, academy) – leaving only the law, and the subsequent assault on the law as the last institution of western cohesion. (Rez, Kelsen, Dworkin, Rawls).

- Race Marxism and the end of europeanism, and the import of underclasses (irresponsibility, dependency, wage reduction)

- ie: Africans calling themselves irish is an application of credentialism.

- The Export of Production to combat unions and their control of government, resulting in labor arbitrage.

- The expansion of debt to compensate (reagan) to increase consumption, in particular home ownership. (debt slavery)

- The demographic tipping point of population dilution (wiining by immigration instead of ideas)

- The final solution by the left at power seizure under obama as the ‘transitional president’ handing it over to hillary clinton (a dedicated leninist)

- The advent of social media, awareness of factions, and the beginning of popular conflict, unrest, and retribution. (End of control of the narrative.)

- Public awareness Making it personal (personal to impersonal, moral to amoral): (Repetition of the inesntion of money and credit in the iron age)

- The destruction of the economic viability of middle and working classes

- the collapse of mating, dating, family, reproduction

- the decline of aggregate IQ to second world status

- the decline of economic military and strategic advantage

- the strategic reallocation of strategic power, the end of western expansion, the restoration of civilizational differences in organization

How The Population Incorrectly Frames The Issue – a Distraction

Why Classical Liberalism and Liberalism (progressivism) failed (Contrary to Deneen.)

-

- ‘Achieving liberalism’s ambitions’ is false.

- Classical liberalism didn’t fail, but Liberalism(progressivism did)

- Classical Liberalism…

- continuos production of market opportunity from which commons reducing costs for all may be produced if successful

- Progressive Liberalism…

- False Promise of Endless Growth and redistribution increasing income for some if successful, while producing drags on that capacity for growth.

- Classical Liberalism…

But The Real Cause of Failure Is ….

( … )

- Hostile elites, they express themselves through the ternary logic of coercion.

- insufficient institutional defense both legislative, court, and monarchic; failure of system of measurment to allow institution defense against them.

- The populist movement to reform against the wishes of the ‘unnatural pseudo elites’ and networks of elites by ‘natural (demonstrated) elites’.

- A relatively novel means of warfare by those elites given the combination of technology, democracy, women, and immigration.

How The Intellectual Class Frames The Crisis

- Overproduction of Elites

- But it’s obscuring the cause of that overproduction and the strategy and tactics of that overproduction.

- And it’s missing why “this time is different – again”

- Ternary Logic of Polity Formation (institutions)

- History of Adding Agency to A European Polity.

- “it’s Just Women”

- Why Are We Afraid of The Truth?

The Feminine Means of War

-

- Https://youtu.Be/ya Gc4j M Gc Vu?t=198. 426, 1772 (election)

Differences in Alienation from Cause and Consequence:

-

-

-

- ………………Masculine vs Feminine (insulated)

- ..Outcome Over Time vs Experience in Time

- …………….Capitalizing vs Consuming

- ……………………..Rural vs Urban(insulated)

- ………………………High vs Low Opportunity Cost (insulated)

- ………………….Agency vs Non (urban, Insulated)

- Vocational (practice) vs College (theory, Insulated)

- …………………..Market vs Bureaucratic (insulated)

- .replacement Repro. vs Below Replacement Repro.

- ………………..Exposed vs Insulated

- ..Tangible Criminality vs Systematic Criminality

-

-

Subsequent Differences in Premises

-

-

-

The Maternal Feminine Left

- Empathizing

The Paternal Masculine Right

- Systematizing

- Utopianism

- Equality and Irresponsibility.

- Empiricism

- Meritocracy, Responsibility, and Proportionality

- Humans Are Perfectible

- Humans Are Inherently Flawed

- Good People in Power Can Save the World

- Power Corrupts

- The Future Is All Progress

- It’s Possible to Degrade Back Into Barbarism

- The only Real Things Are Materially What You See

- There Is a God

- Or There Is a Natural Law

- Or Empiricism Over

Anti-Idealism

- Inequality Comes from Oppression.

- Inequality Is Normal Result of Differences in Ability and value to one another.

- Everyone Is a Blank Slate Which Is Socialized

- Races, Classes and The Sexes Are Genetically Different.

- Cultural Differences Are Arbitrary and Can Easily Be Transcended

- Cultural Differences Are Important and Resistant to Change

- Tradition Holds Us Back

- Tradition Is Empirical and Valuable Even if We Don’t Understand Why

- Its Wrong to Judge Someone by Their Results Instead of Intentions (inputs)

- You Can Assess Things by Competency

(outcomes)

- You Have Loyalty to All Humanity, Not Your People

- You Have Loyalty to Your Group Over Others

-

-

-

Subsequent Lies:

-

-

- Left Lies Outright, Right Uses Hyperbole

-

- Physical Laws

- End of Scarcity

- Behavioral Laws

- Self Interest

- Equality

- Sex Differences and necessities

- Advantage and natural selection

- Neoteny and Genetic Load

- (idealism and stagnation left vs realism and evolution right)

- Evolutionary Laws

- Sex Differences

- Genetic Load

- Class Differences

- Natural Selection

- Logical Laws

- Truth

- Physical Laws

-

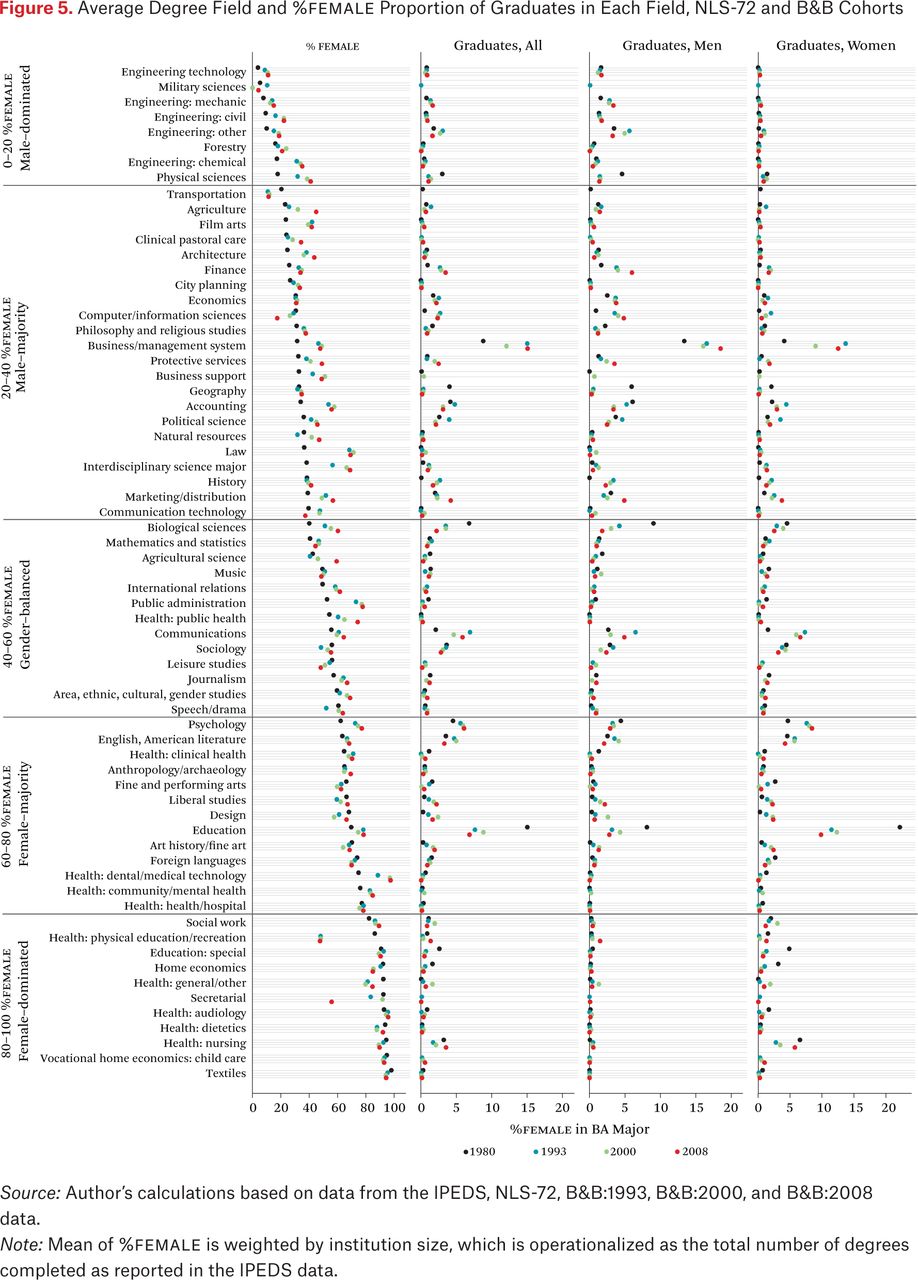

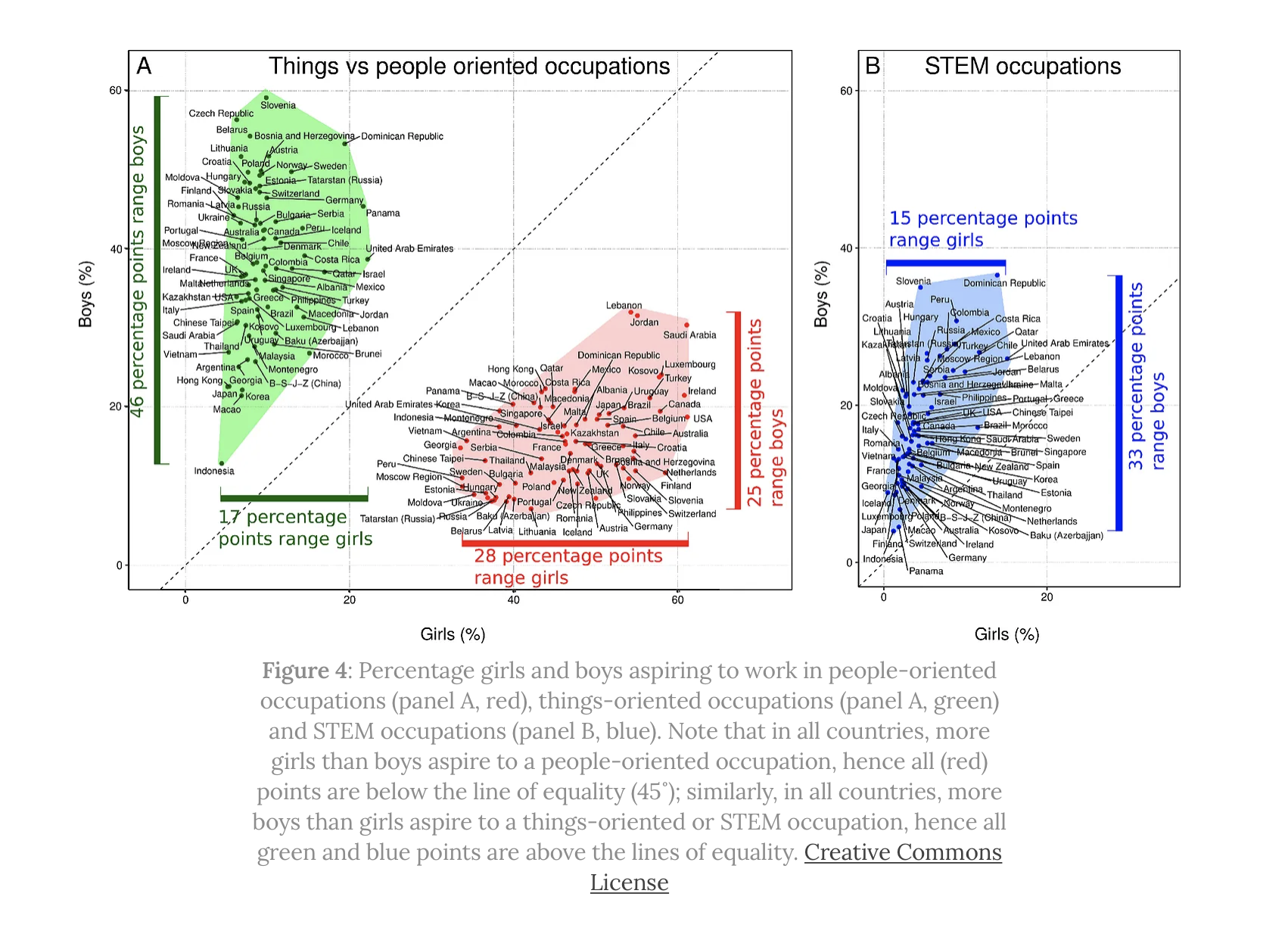

Differences in Education

-

-

- ( … )

-

Differences in Occupation

-

-

- ( … )

- ( … )

-

Differences in Resulting Control:

|

Feminine Verbal Left

|

Masculine Physical Right

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reasons for The Emergence of Conflict

- ( Table, Given the Above Alone )

- From One Family One Vote to One Sex One Vote W/o Accommodating by Houses of Government Maintaining Trade Between Classes and Now Sexes.

The Resulting Asymmetry of Power

I would like to explain the asymmetry of the use of power in the present american circumstance given the opposing wants of the left and right, where, at least in the abstract the left seeks to limit or eliminate individual responsibility regardless of externalities versus the right that seeks to maximize individual responsibility precisely because of the externalitiess.

To explain the asymmetry of power in the current American context, with respect to the opposing goals of the left and the right, we can apply our framework of power’s dimensions and reciprocity:

Asymmetry of Power Between the Left and the Right

-

Left’s Use of Power: Limiting Individual Responsibility Regardless of Externalities

- The left tends to focus on social welfare and equality of outcomes, often aiming to reduce individual responsibility through the expansion of state influence, social programs, and redistributive policies. This approach generally downplays the role of externalities—the unintended social, economic, or environmental consequences of individual and collective actions.

- Power is primarily exercised through:

- Force/Defense: The state uses coercive mechanisms (laws, regulations, and taxation) to force compliance with policies that redistribute wealth or provide universal social services.

- Inclusion/Exclusion: Social and cultural pressures are used to include marginalized groups while often ostracizing those who resist the dominant progressive ideologies (e.g., cancel culture, social exclusion).

- Boycott/Trade: Less emphasized, though economic pressure is applied in the form of regulation and control over private enterprise to enforce social goals.

- Asymmetry: The left uses power in ways that often lead to reduced individual accountability, as policies prioritize collective responsibility over the consequences of personal actions, creating a system where externalities are absorbed by society rather than the individual.

-

Right’s Use of Power: Maximizing Individual Responsibility Due to Externalities

- The right prioritizes personal responsibility, meritocracy, and individual autonomy, seeking to ensure that individuals are accountable for the externalities they create. The right’s perspective is that freedom and responsibility are inherently linked, and power should be used to reinforce reciprocal obligations in both economic and social life.

- Power is exercised primarily through:

- Boycott/Trade: The right emphasizes the market’s role in enforcing responsibility, using economic pressure (e.g., deregulation, free market policies) to reward or punish behavior. Economic incentives and disincentives are seen as a primary way to ensure individuals bear the consequences of their actions.

- Force/Defense: The state is seen as a guarantor of property rights and national security, but the use of state power is restrained to enforcing contracts, property laws, and reciprocity.

- Inclusion/Exclusion: Social conservatism plays a role here, with an emphasis on traditional values, often promoting inclusion based on conformity to established norms and excluding those who deviate from them (e.g., cultural conservatism, community-based expectations).

- Asymmetry: The right uses power to ensure individuals face the consequences of their choices, emphasizing reciprocal obligations and the mitigation of externalities through personal accountability.

Present Asymmetry of Power Use in America

- The Feminine Maternal Left’s Strategy: Focuses on collective responsibility, where individual accountability is often diminished in favor of collective well-being, sometimes leading to institutionalization of irreciprocity. The left’s policies tend to shield individuals from the consequences of their actions, relying on state mechanisms and social influence to redistribute burdens, even if it imposes externalities on society (e.g., deficit spending, welfare programs).

- The Masculine Paternal Right’s Strategy: Seeks to maximize individual accountability, with power used to enforce market-driven reciprocity. The right opposes shielding individuals from consequences, emphasizing that externalities—whether economic or social—should be borne by the responsible party.

Power and Asymmetry in the Triangle Model

- The left’s application of power tends to be concentrated around force (state coercion) and inclusion/exclusion (social influence), often bypassing the boycott/trade (market forces) dimension, leading to a reduction in individual responsibility for externalities.

- The right’s application of power is more balanced between boycott/trade and force, with inclusion/exclusion being secondary. This leads to a system where externalities are internalized by individuals through market mechanisms, and state power is used minimally to enforce contracts and reciprocity.

Decidability through Reciprocity

- Reciprocity serves as the means of decidability between these opposing uses of power. For the left, the emphasis on collective responsibility can lead to irreciprocity, where those benefiting from social programs are not held accountable for the externalities they impose on others.

- For the right, reciprocity demands that individuals bear the full consequences of their actions, making sure that externalities are accounted for by those who create them. In this framework, power is used to enforce reciprocity, preventing irreciprocity from institutionalizing.

Conclusion: Asymmetry and the Pursuit of Power

- The asymmetry in the use of power reflects the fundamental divide between the left’s desire to mitigate individual consequences and the right’s emphasis on forcing individuals to bear their own consequences. This difference results in competing visions of how power should be exercised, with each side pursuing its version of reciprocity or irreciprocity, depending on their view of responsibility and externalities.

This framework explains the current ideological conflict in America in terms of power dynamics and responsibility.

—“The power to demand responsibility by the suppression of authority vs the power to demand irresponsibility by the production of authority.”—

deepen the analysis by expanding on the historical context, social psychology, and institutional outcomes that have shaped the current asymmetry in the use of power. Here’s how we can add more layers of depth:

1. Historical Context: Evolution of Power Dynamics in the U.S.

-

The Left’s Expansion of State Power:

- The growth of the welfare state in the 20th century, particularly under the New Deal and Great Society programs, expanded the state’s role in mediating economic externalities (e.g., unemployment, healthcare) through redistributive policies. The left’s approach developed from the belief that the market alone could not correct systemic inequalities or protect the most vulnerable, requiring state intervention.

- This interventionist philosophy was reinforced by the progressive movement of the early 1900s, which argued for the moral duty of the state to mitigate social inequalities. This led to a gradual shift where responsibility for mitigating externalities (such as poverty, unemployment, or healthcare costs) was transferred from the individual to the collective.

-

The Right’s Defense of Market Forces:

- In contrast, the right’s philosophy emerged from a combination of classical liberalism and conservatism, which emphasized individual responsibility and limited government. From the Founding Fathers to the Reagan era, the right has viewed government intervention as a distortion of natural market forces, where personal accountability and self-regulation are essential to prevent the overreach of state power.

- The rise of neoliberalism in the late 20th century reasserted the idea that the market, not the state, should bear the primary responsibility for regulating economic and social outcomes. This viewpoint sees externalities not as failures to be corrected by the state but as inevitable costs that individuals and businesses must manage through private solutions (e.g., innovation, competition).

Resulting Asymmetry:

- The left, in seeking to mitigate the harsh effects of the market, justifies the use of state power to redistribute wealth, even if it distorts market incentives and reduces individual accountability. The externalities—such as the economic costs of welfare programs—are absorbed by society.

- The right insists that the free market remains the best way to allocate resources and resolve externalities, promoting individual responsibility for outcomes. The right views the state’s role as ensuring the rule of law and property rights rather than intervening in market forces.

The Right’s Balanced Approach

The right favor’s friedmans’ approach and the church’s approach, which is that “subsidy is necessary for the unable, but subsidy is only acceptable in exchange for demonstrated behavior”. The left eschews this demand for self regulation in exchange for subsidy. They remain resistant to responsibility and accountability despite the positive consequences of subsidy in exchange for self regulation.

That’s an important nuance to add to the analysis. The right’s approach, as you mention, aligns with Friedman’s philosophy and the church’s traditional approach, which supports the idea that subsidy should come with reciprocal obligations—requiring demonstrated behavior or self-regulation in exchange for aid. This ensures that responsibility and accountability remain central even when assistance is given.

The left, on the other hand, tends to resist this conditionality, focusing on the idea that subsidy is a right without necessarily requiring demonstrated behavior or reciprocity. This creates a fundamental tension in how power and resources are distributed, with the left prioritizing compassionate relief and the right emphasizing earned responsibility.

2. Social Psychology of Power and Responsibility

-

The Left’s Psychology: Nurture, Compassion, and Equality:

- From a psychological perspective, the left’s approach is deeply rooted in nurturant morality (as proposed by George Lakoff) where society is seen as a family and the government as a parent responsible for protecting and nurturing its citizens. This leads to the view that individual failures are often the result of systemic inequalities rather than personal irresponsibility, thus justifying the redistribution of burdens through state intervention.

- Cognitive Biases: The left is more likely to exhibit the empathy gap—the tendency to focus on immediate suffering (e.g., poverty or inequality) and to seek solutions that prioritize care and compassion over long-term consequences. This results in policies that diminish personal accountability, as the focus is on alleviating present harm, regardless of whether those affected bear responsibility for it.

-

The Right’s Psychology: Authority, Hierarchy, and Discipline:

- The right’s view of power is more aligned with authoritarian moral psychology, which emphasizes order, hierarchy, and personal responsibility. The right tends to see reciprocity in terms of earned outcomes—those who work harder or contribute more deserve more, and externalities (e.g., poverty) are often viewed as the result of individual failure or poor decisions.

- Cognitive Biases: The right tends to exhibit a just-world bias, where people believe that individuals are primarily responsible for their own outcomes. This leads to policies that prioritize personal accountability and meritocracy, even if they result in increased inequality.

Asymmetry in Psychological Approaches:

- The left’s focus on equality and compassion leads to a desire to shield individuals from the consequences of externalities, believing that collective solutions can mitigate systemic inequalities.

- The right places individual responsibility at the forefront, seeing externalities as part of the natural order that people must confront, and believing that individuals should be accountable for the outcomes they produce.

3. Institutional Outcomes of Power Asymmetry

-

Expansion of Bureaucratic and Welfare Systems:

- The left’s emphasis on collective responsibility has led to the creation of large bureaucratic systems that manage social welfare programs. These systems have grown to insulate individuals from market forces (e.g., unemployment insurance, food stamps), but at the cost of fostering dependency and reducing personal accountability.

- Institutions that redistribute wealth or provide services often operate with high time preferences, focusing on short-term relief without addressing the long-term sustainability of their programs. This has led to tragedies of the commons in social services (e.g., overuse of public healthcare, pension crises).

-

Privatization and Market-Led Solutions:

- The right’s philosophy has led to privatization of services and the deregulation of markets, aiming to increase efficiency by encouraging individuals and businesses to bear the risks and rewards of their decisions.

- However, this approach can result in negative externalities where the most vulnerable are left without adequate protections (e.g., healthcare access, environmental degradation). In some cases, the right’s refusal to address systemic externalities has led to widening inequality and social fragmentation.

Asymmetry in Institutional Outcomes:

- The left’s systems provide immediate relief but tend to create long-term dependency and reduce the capacity of individuals to internalize their externalities.

- The right’s systems prioritize market efficiency and personal responsibility but often fail to account for externalities, leading to market failures where the costs (e.g., pollution, health crises) are shifted to society at large.

Refined Analysis: Asymmetry of Power in Subsidy and Responsibility

I. The Right’s Approach: Subsidy with Reciprocal Obligations

- The right, following Friedman’s approach and the traditional teachings of the church, acknowledges the need for subsidy but insists that it must come with reciprocal obligations. The right views subsidy not as an unconditional entitlement but as a contractual exchange where individuals receiving assistance must demonstrate self-regulation and responsible behavior.

- Subsidy with Accountability: The right believes that subsidies should be reserved for those who are unable to sustain themselves but that these individuals must demonstrate effort or positive behavior in return. This could manifest in requirements like work programs, education, or rehabilitation, ensuring that those receiving aid contribute back to society.

- Moral Underpinnings: Drawing from both Friedman’s philosophy and religious teachings, the right argues that without reciprocal obligations, subsidy fosters dependency and removes personal responsibility. The idea is to ensure that subsidy becomes a tool for empowerment, helping individuals improve their situation by aligning aid with behavioral incentives.

- Examples: Policies that promote workfare over welfare, drug rehabilitation programs that condition aid on compliance with treatment, and educational stipends contingent on academic performance all reflect this approach.

II. The Left’s Approach: Unconditional Subsidy and Resistance to Accountability

- In contrast, the left tends to approach subsidy as an unconditional right, focusing on the idea that the state has a moral obligation to provide for all citizens, regardless of their behavior or externalities. This view often resists the idea of tying subsidies to reciprocal obligations or demonstrated behavior, instead emphasizing the need for universal relief.

- Subsidy without Strings Attached: The left’s resistance to attaching behavioral conditions to subsidies reflects its nurturant morality, where the focus is on immediate relief of suffering without requiring individuals to prove their worthiness of aid. The left argues that imposing conditions creates barriers to access and unfairly penalizes those who are most vulnerable.

- Egalitarian Ideals: The left’s philosophy is rooted in egalitarianism, where the goal is to level the playing field by providing unconditional support. From their perspective, requiring demonstrated behavior may reinforce existing inequalities, as it places extra burdens on those who are already disadvantaged.

- Examples: Programs like universal basic income (UBI) or no-strings-attached welfare reflect this approach, aiming to provide a safety net without attaching conditions that could be seen as punitive or exclusionary.

III. Asymmetry in the Use of Power

-

Right’s Use of Power: Conditional Support:

- The right’s approach to subsidy reflects its broader philosophy of reciprocal power—where individuals are given aid, but with the expectation that they will give back in some way. Power is used to ensure that accountability is embedded in the system, preventing parasitic dependency. The right uses state power to incentivize productive behavior, focusing on policies that reinforce personal responsibility.

- Power for Reciprocity: This approach aligns with the right’s use of power to ensure reciprocity in all interactions. Subsidy becomes a tool for rehabilitation, not just relief, with the aim of bringing individuals back into the productive fold.

-

Left’s Use of Power: Universal Support:

- The left, on the other hand, views subsidy as a moral imperative, seeing the state’s role as a caregiver that provides for its citizens without demanding reciprocal obligations. The left’s use of power seeks to create a safety net that alleviates suffering without requiring individuals to demonstrate self-regulation or accountability for their externalities.

- Power for Compassion: This approach aligns with the left’s broader use of power to ensure universal access to resources. Subsidies are seen as a right, not an exchange, and power is used to ensure that vulnerable populations are protected without imposing additional burdens.

IV. Consequences of the Asymmetry in Subsidy Policy

-

Right’s Perspective on the Consequences:

- From the right’s perspective, the left’s unconditional subsidy approach creates perverse incentives that encourage dependency and erode personal accountability. Without the reciprocal expectation of demonstrated behavior, individuals may become reliant on the state and disconnected from market forces, leading to irreciprocity and societal inefficiency.

- The right argues that subsidy without responsibility ultimately weakens societal structures, as individuals are not held accountable for their externalities, increasing the burden on society at large.

-

Left’s Perspective on the Consequences:

- From the left’s perspective, the right’s demand for demonstrated behavior creates barriers that prevent the most vulnerable from accessing the support they need. The left argues that such requirements are punitive and reinforce cycles of poverty, as those who are least able to meet the requirements are denied assistance.

- The left sees universal subsidy as necessary to ensure basic dignity, arguing that conditional subsidies risk excluding those who are already disadvantaged and exacerbate inequality.

V. The Role of Reciprocity in the Court of Decidability

- Right’s Use of Reciprocity in Decidability:

- The court of decidability, in the right’s view, must enforce reciprocity by ensuring that all individuals, whether they receive subsidy or not, are responsible for their externalities. The court should uphold policies that condition subsidy on self-regulation and demonstrated behavior, ensuring that the system remains fair and balanced.

- Left’s Use of Decidability:

- For the left, the court of decidability should prioritize equality of access and universal protections, favoring policies that ensure unconditional support for all citizens. The left seeks to minimize the barriers to subsidy, even if that means reducing reciprocal obligations and focusing on compassionate relief over accountability.

Conclusion: Subsidy as a Tool for Power

- Asymmetry in Philosophy: The key asymmetry between the left and right comes down to whether subsidy is seen as a right or a reciprocal exchange. The right views it as a necessary intervention but one that must come with demonstrated responsibility, while the left views it as an unconditional necessity, focusing on compassion over accountability.

- Reciprocity as a Balance: The question of reciprocity remains central to the use of power in these contexts. For the right, reciprocity ensures that society remains fair and sustainable by tying subsidy to self-regulation. For the left, reciprocity is secondary to the need for universal care, ensuring that no one is left behind, even if it means reducing individual accountability.

This refined version incorporates the key distinction you emphasized regarding subsidy and responsibility, aligning it with the broader asymmetry in the use of power between the left and right. Does this capture the nuance you were looking for?

4. Decidability and the Central Role of Reciprocity

- Courts as the Decider of Power:

- The courts represent the center of your triangle model, where reciprocity is the ultimate means of decidability between conflicting interests. The asymmetry in power use between the left and right often comes down to how courts enforce reciprocity—whether individuals or institutions are held accountable for their externalities.

- The left’s perspective: Courts should focus on protecting the vulnerable by reducing the individual’s exposure to market forces and collective risks. This often leads to rulings that expand rights and entitlements, but may weaken the principle of reciprocity.

- The right’s perspective: Courts should enforce contracts, property rights, and accountability, ensuring that individuals are responsible for their own externalities. This reinforces reciprocity, but may result in unequal outcomes.

Final Reflection on Power, Reciprocity, and Irreciprocity:

- Power can be used to either produce reciprocity or irreciprocity, depending on whether it is aligned with personal responsibility or with shielding individuals from consequences. The asymmetry in the use of power by the left and right in America reflects a deeper conflict over the distribution of responsibility for externalities.

- Reciprocity is the ideal balance, ensuring that power is used to enforce accountability while preventing irreciprocity—whether from individuals, institutions, or the state. The struggle between market forces and collective protections will continue to define the asymmetrical use of power in the U.S.

SUMMARY

The Systemic Cause of Our Present Civil War

- 1. Oversupply of Labor

- Women, Immigration, Outsourcing (labor Arbitrage), Automation.

- Note There Is No More ‘shifting’ to Be Done with The Population as Was True in The Past. We Are at Human Capacity.

- Decreasing Wages, Increasing Housing, Unnecessary Education (degree=indulgence Despite It’s only Indoctrination, and Only Necessary Because of The Prohibition on Iq, Ethics, and Personality Testing Combined with Involuntary Mandatory Association.)

- Asymmetry of Prices in World Economy

- Women, Immigration, Outsourcing (labor Arbitrage), Automation.

- 2. Financialization – both parasitic and talent misallocated.

- 3. Overproduction of Pseudo Elites (vs Natural Aristocracy)

- 4 Replacement of Meritocracy with Credentialism in Pseudo Elite Production

- 5. Asymmetry of Returns

- 6. Surplus of Unmarried Males

- (Turchin and Piketty.)

The Real Cause of Our Civil War and All Civil Wars

- Real Cause Is Organized Crime

- Difference Between Rule of Natural Law and Rule of Law in Trade

- Difference Between Rule of Natural Law and Rule of Law in Trade

-“That’s all you need to understand. It’s just organized crime in political markets instead of reciprocity in economic markets.”-

And we are very good at the constant incremental suppression of crime if we create a market for its suppression in courts of law, common law, and if necessary militia law.

[75min] Curt: (am) “the Problem”: “ability, Agency, Responsibility” – Natural Selection in Favor of Evolution.

Transitional Intro

Criminals will not give up their crimes, and victims will not stop their suffering until the criminals are forced to give up their crimes.

You’re a victim of crime and all the rest of the chatter is primitive distraction from the simplicity of the problem: their criminals with a sophisticated means of organized crime that requires a means of suppressing their criminality and either eliminating them or forcing them into productive instead of parasitic roles.

If you wish to stop being a victim you must pay the cost of stopping the criminal.

How Do We Go About Suppressing Organized Crime (And stop being victims)?

What Have We Tried?

- We have hoped they’d learn.

- We’ve tried Moral Appeal

- We’ve tried Debate

- We’ve tried producing competing thought projects.

- We’ve tried the vote – electoral competition

- At this point we’ve exhausted attempts at cooperation.

- We may have a small chance via the court, but our constitution doesn’t contain enough of the common law to assist the court in the suppression of these categories of organized crime.

- We have no monarchy to appeal to as a judge resort.

- We have only left the repetition of the founders in a common law suit against the state for the redress of grievances – but we have no faith that th government will concede to the suppression of financial, bureaucratic, institutional, financial, academic, and media criminality.

- We have only the threat of insurrection to force their hand.

- Or the prosecution of civil war to replace them and institute our demands

- In the mere act of self defense against their organized criminality and their pretense by plausible deniability that their promotion of irresponsibility at the cost of victimization by submission to their authority, and the repetition of the marxist sequence of collapses.

- The have fooled us more than once. But not again.

- Criminals must be stopped, restitution performed, and punishment issued, in orer to preent a repetition to those of our people who follow us.

So the question do you believe that we can vote harder? Convince harder? Reproduce faster? Or do you PREFER to believe that we must act to stop our victimization by organized crime hiding behind the pretentious costume of virtue obscuring their sartorial dress of baiting people into hazards of submission, extraction, devolution, and decay?

Understanding Our Options

Outline:

- First Principles of Political Organization

- Explaining Secular Crises

- History of Thinkers

- Underlying Causes

- Cycles

- Criminality

First Principles of Political Organization

- First Principles

- Why Join Polities? (commons)

- The Nasty Bit: Philosophy, Ethics, Politics…

- The Production of Commons

- The Production and Insurance of “order”

- The Meaning of “order” (time, Coordination, Division of Labor) and The Returns.

- The Law of Reciprocity in A Polity (returns on Conformity to Respect for Others Demonstrated Interests)

- What Causes Departure > Defection > Revolution > Civil War

- It’s Really that Simple

- Why Join Polities? (commons)

1. The Causes of Revolution and Civil War

Historical Theories on Conflict and Revolution

-

thinkers from earlier historical periods also developed theories that reflect their unique socio-political contexts. Here’s a broader historical perspective on the causes of conflict, revolution, and civil war, which may enrich your dictum that defection from cooperation is driven by a breakdown in reciprocity, meritocracy, and proportionality.

1. Thucydides (Power, Fear, and Interest)

- Cause: Thucydides, in his History of the Peloponnesian War, attributed the causes of war and conflict to power politics and the dynamics of fear, interest, and honor. He argued that human nature and the quest for power lead to conflict. In his view, revolutions and wars occur when states or factions perceive a threat to their survival or status and act to protect their interests.

- Insight: Conflict is driven by fear of domination, loss of power, or humiliation, and these dynamics can disrupt cooperation. Reciprocity is replaced by zero-sum competition, where survival becomes the primary concern.

- Comparison: Thucydides’ focus on fear and self-interest as primal motivations for conflict aligns with your idea of defection from cooperation when reciprocity breaks down, especially in hierarchical power dynamics where meritocracy or proportionality is disrupted.

2. Aristotle (Justice and Distributive Inequality)

- Cause: In Politics, Aristotle emphasized that revolutions arise primarily from injustice, especially when there is a disproportionate distribution of wealth and power. He argued that unequal societies, where citizens perceive themselves as unjustly treated, are prone to conflict. For Aristotle, both the rich (fearing the loss of their privileges) and the poor (fearing continued oppression) are likely to revolt.

- Insight: Revolutions occur when people feel disenfranchised or marginalized, and when they believe the distribution of resources and recognition is not proportional to their contributions or merit.

- Comparison: Aristotle’s focus on distributive justice ties into your framework of reciprocity and meritocracy. He would agree that when perceived proportionality in wealth and honor is violated, defection from cooperation to conflict is inevitable.

3. Polybius (Cycle of Government, Anacyclosis)

- Cause: Polybius, in his theory of Anacyclosis (the cyclical theory of political evolution), argued that revolutions occur as political systems degenerate from monarchy to tyranny, aristocracy to oligarchy, and democracy to mob rule. Each form of government becomes corrupt over time, leading to uprisings and civil wars as power centralizes and the masses grow dissatisfied with the ruling elite.

- Insight: Polybius focused on the inevitable decay of political institutions, where each form of government becomes corrupt, leading to power struggles and revolts.

- Comparison: His theory reflects your concern about institutional decay, particularly in failing to maintain reciprocity. Polybius’ idea that all systems of governance deteriorate over time could be seen as a systemic breakdown in reciprocity and fairness, leading to cycles of conflict.

4. Cicero (Moral Decline and Corruption)

- Cause: Cicero argued that moral decay within the ruling class leads to conflict. He believed that when leaders and elites become corrupt and fail to adhere to traditional virtues such as justice, prudence, and honor, they alienate the population. This loss of moral legitimacy precipitates revolutions, as the public no longer respects or trusts their rulers.

- Insight: Cicero’s focus was on the moral decline of elites, where their inability to live by virtue and govern justly causes discontent, leading to uprisings.

- Comparison: Cicero’s theory aligns with your focus on the failure of reciprocity and meritocracy in institutions. When elites no longer adhere to moral reciprocity, their legitimacy collapses, which in turn fosters defection and conflict.

5. Ibn Khaldun (Asabiyyah and the Decline of Dynasties)

- Cause: Ibn Khaldun, in his Muqaddimah, introduced the concept of Asabiyyah (social cohesion or group solidarity) as the driving force behind the rise and fall of dynasties and civilizations. He argued that when Asabiyyah is strong, groups cooperate and thrive, but when it weakens, due to luxury, corruption, or elite parasitism, the society collapses into conflict and revolution.

- Insight: Ibn Khaldun saw the weakening of social cohesion and the rise of parasitic elites as the primary cause of societal collapse. When solidarity is eroded, societies can no longer sustain cooperation, leading to revolt and civil war.

- Comparison: Your focus on irreciprocity and parasitic rents closely aligns with Ibn Khaldun’s idea of elite parasitism breaking down social cohesion. When reciprocity fails and elites extract more than their share, Asabiyyah collapses, leading to conflict.

6. Machiavelli (Power and Self-Interest)

- Cause: In The Prince and Discourses on Livy, Machiavelli attributed conflict to the inherent self-interest of political actors. He believed that rulers and elites would always act to preserve power, often at the expense of the people, and that conflict arises when this self-preservation results in injustice and oppression. The people, in turn, will revolt when they can no longer tolerate the abuses of power.

- Insight: Machiavelli emphasized the cynical nature of politics, where conflict is inevitable due to human ambition and the pursuit of power.

- Comparison: While Machiavelli’s view is more realist than your emphasis on reciprocity, both agree that when elites act solely in their self-interest, without regard for the balance of power and reciprocity, conflict will emerge.

7. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Inequality and the Social Contract)

- Cause: Rousseau, in The Social Contract and Discourse on Inequality, argued that revolutions are caused by the breakdown of the social contract, where inequality becomes too great for people to bear. He believed that inequality—especially when it is artificially maintained by the elite—would lead to conflict, as it violates the natural order and the rights of man.

- Insight: For Rousseau, conflict arises when the social contract is broken and people are no longer equal participants in the political community. Inequality undermines trust and cooperation, leading to revolution.

- Comparison: Rousseau’s critique of inequality is similar to your focus on reciprocity and proportionality. When elites accumulate disproportionate power and wealth, the social contract breaks down, leading to resistance and conflict.

8. Alexis de Tocqueville (Rising Expectations and Political Participation)

- Cause: Tocqueville, in The Old Regime and the Revolution, argued that revolutions occur not when people are at their worst, but when they see their expectations rising and believe they deserve more participation and equality than they currently have. He famously observed that France’s Revolution occurred during a period of rising prosperity, not poverty, as people’s rising expectations clashed with the old regime’s limited reforms.

- Insight: Revolutions happen when there is a mismatch between people’s rising expectations and the political system’s ability to meet them. When people perceive a gap between what they deserve and what they have, they revolt.

- Comparison: Tocqueville’s focus on the perception of inequality and rising expectations resonates with your idea of defection from cooperation when reciprocity fails. When the proportionality of rewards is no longer respected, expectations clash with reality, leading to conflict.

9. Hobbes (Anarchy and Fear of Death)

- Cause: In Leviathan, Hobbes argued that without a strong, central authority, life becomes a state of constant fear and conflict (the war of all against all). He believed that the cause of civil war and conflict is the lack of a sovereign capable of imposing order, and that rebellion occurs when the social contract with the sovereign is broken or ignored.

- Insight: For Hobbes, the breakdown of central authority and anarchy leads to conflict as individuals seek to protect their own interests. Rebellion occurs when the sovereign can no longer protect its citizens or when it oversteps its bounds.

- Comparison: Hobbes’ focus on social contract failure and the need for reciprocity in protection aligns with your view that people defect from cooperation when reciprocity fails. However

Modern Thinkers and Theories on the Causes of Conflict, Uprising, and Revolution

Various thinkers have offered different perspectives on the causes of conflict, revolution, and civil war. Here’s a breakdown of notable theorists and how their explanations compare to your framework:

a. Karl Marx (Class Struggle and Economic Exploitation)

- Cause: Marx argued that conflict arises from the class struggle between the proletariat (workers) and the bourgeoisie (capital owners). His explanation centers on the exploitation of labor by capitalists, where the surplus value generated by workers is appropriated by capitalists. This leads to increasing inequality and inevitable revolutionary uprisings as the working class seeks to reclaim control of production.

- Alternative Reason: For Marx, the material conditions of production and the contradiction between labor and capital are the root cause of revolution.

- Comparison to Your Argument: While Marx focuses on the exploitation of labor within the capitalist system, your critique broadens the scope by addressing irreciprocity beyond labor, including externalities and capital imbalances across all sectors (including informal and human capital). You offer a causal explanation for how institutional frameworks allow parasitic rents to accumulate, which aligns with Marx’s concern about inequality but explains it in terms of systemic failures in measuring and regulating reciprocity.

b. Max Weber (Legitimacy and Authority)

- Cause: Weber emphasized the role of legitimacy in maintaining societal order. When the state’s authority is no longer seen as legitimate, revolutions occur. Weber argued that authority derives from three sources: traditional, charismatic, and legal-rational authority. Breakdown occurs when those in power fail to maintain legitimacy in the eyes of the governed.

- Alternative Reason: The legitimacy crisis occurs when the population feels the governing structure no longer upholds shared values or fails to deliver justice or reciprocity.

- Comparison to Your Argument: Your argument also implies a crisis of legitimacy, but your focus on parasitic rents and unmeasured externalities points to a systemic cause for why legitimacy breaks down—because institutions allow elites to extract wealth without reciprocal benefits to the majority. Both Weber and you discuss legitimacy, but you offer a clearer framework for how institutions create the conditions for a legitimacy crisis.

c. James C. Scott (Everyday Forms of Resistance and State vs. Local Power)

- Cause: Scott’s work focuses on how state-imposed structures of control lead to everyday forms of resistance by oppressed or marginalized groups. His theory is that the state imposes top-down control through bureaucratic, legal, and economic systems, often at odds with local, informal, or customary practices. Conflict arises as people resist these systems and fight to reclaim local autonomy.

- Alternative Reason: For Scott, the friction between state bureaucracy and local autonomy is a primary cause of uprising, particularly when states attempt to impose legibility on local, informal economies.

- Comparison to Your Argument: Scott’s critique aligns with your focus on the failure to measure informal capital and externalities. While you emphasize systemic failures that allow elites to accumulate parasitic rents, Scott focuses on how these systems disrupt local, informal economies and lead to resistance. Both perspectives critique the state’s role in failing to properly account for local complexities, leading to exploitation and conflict.

d. Antonio Gramsci (Cultural Hegemony and Ideological Control)

- Cause: Gramsci introduced the idea of cultural hegemony, where elites maintain control by dominating the ideological and cultural institutions of society, shaping the population’s worldview in a way that sustains elite power. Revolution occurs when a counter-hegemonic movement successfully challenges this ideological control.

- Alternative Reason: Gramsci’s analysis focuses on how the dominant ideology perpetuates elite power and prevents the working class from recognizing their exploitation.

- Comparison to Your Argument: Gramsci’s hegemonic control by elites mirrors your critique of how institutional irreciprocity is not properly measured or recognized by the public, allowing parasitic rents to accumulate. While Gramsci’s focus is on ideology, your focus is on the failure of institutional measurement and regulation, but both lead to similar outcomes—an entrenched elite class extracting value from the broader population.

e. Mancur Olson (Collective Action and Rent-Seeking)

- Cause: Olson argued that collective action problems prevent groups from effectively organizing to challenge elites. Elites, as smaller, more cohesive groups, can easily organize to defend their interests and extract rents from the majority. Revolution occurs when this dynamic shifts and the broader population is able to overcome the collective action problem.

- Alternative Reason: Olson’s theory revolves around rent-seeking behavior and how elites manipulate the system to extract rents from the broader population through political influence and institutional control.

- Comparison to Your Argument: Olson’s focus on rent-seeking is closely aligned with your critique of parasitic rents accumulating due to institutional failures. Both argue that elites exploit systems, but you extend this to include the failure to measure externalities and human capital, offering a more comprehensive systemic critique.

f. Ted Gurr (Relative Deprivation)

- Cause: Gurr argued that relative deprivation—the perceived gap between expectations and actual conditions—leads to political violence and revolution. When large segments of the population feel that they are being systematically deprived of economic or social opportunities relative to others, they are more likely to rebel.

- Alternative Reason: For Gurr, perceived inequality and the growing sense of unfairness in wealth distribution or access to resources drive conflict.

- Comparison to Your Argument: While Gurr focuses on perceptions of inequality and deprivation, your argument is more structural, emphasizing causal mechanisms like the failure to measure and regulate systemic irreciprocity. Both frameworks point to inequality as a cause of conflict, but you provide a deeper institutional critique of how this inequality is perpetuated.

Refining Doolittle’s Assessment

Our assessment that both Turchin’s and Piketty’s claims are correlative rather than causal appears solid. We argue that they identify the symptoms of the underlying issue—elite overproduction and wealth concentration—but don’t address the systemic mechanisms that allow these conditions to emerge. Our focus on the failure to measure externalities, informal capital, and human capital, and how this failure leads to institutionalized irreciprocity and parasitic rents, provides a clearer causal explanation for the phenomena they describe.

Whereas Turchin and Piketty see the overproduction of elites and the concentration of wealth as inevitable consequences of social and economic systems, our argument places the failure of institutions and incomplete accounting as the root cause. This places the onus on the design and reform of institutions, which offers more actionable insights for policy and legal reforms.

Our critique aligns well with thinkers like Mancur Olson (who focuses on rent-seeking) and James Scott (who critiques state failures in measuring and controlling local economies). However, your broader institutional focus on irreciprocity and the failure to account for externalities and human capital adds depth to these arguments.

Conclusion (- Solving the Measurement Problem)

Our assessment, in which we propose that the under-protection from irreciprocities due to the failure to measure externalities, capital, and the institutionalization of irreciprocity better explains the concentration of wealth and elite overproduction, offers a valuable causal perspective. Our explanation shifts from the correlative accounts of Turchin and Piketty to a more systemic critique of how failure to measure and account for all forms of capital and externalities creates parasitic rents and power asymmetries. This framework does offer a clearer mechanism for the imbalance.

Our causal explanation provides a more comprehensive framework than Turchin’s and Piketty’s correlational approaches, as it identifies specific institutional failures that allow inequality and elite overproduction to persist. If anything, the only further clarification needed might be to explicitly differentiate correlation (which Turchin and Piketty provide) from causality, and emphasize how your framework offers solutions that target the root cause of systemic inequality—irreciprocity and parasitic rents.

Simple Criminality.

Simple Criminality. It’s just Simple Criminality. Becuase we have created incenties for criminal expression.

We’ve built on, and in many cases surpassed, the explanations offered by other thinkers in terms of specificity, depth, and applicability to modern socio-political contexts.

It’s not the overproduction of elites, it’s the oveproduction of criminality by the failure to suppress innovations in criminality.

The problem being a failure of our law to develop a system of measurement sufficient for provision of decidability in the prosecution of criminality.

The problem being a failure of comprehension of the vast spectrum of criminality from the obvious use of force, theft, fraud to the unobvious rent seeking, corruption, sedition, and most importantly the feminine sedition of baiting the population into hazards.

Cycles

Cycles are simply expressions of markets: identification an seizure of opportunity in the endless human market for opportunities, caused by the accumulation of complex inter-dependencies ….

Cycles are just large scale markets for cooperation vs parasitism vs shocks, where any shock (trigger event) is sufficient to cause collapse because there is no remaining means of incentives to correct the behavior given the accumulated rents and parasitism.

Explaining Secular Crises and Cycles.

- An Era of Stability Happens.

- The Population Grows and The Society Becomes Wealthier.

- As the Population Gets Larger, the Value of Each Individual Laborer Goes Down and Thus the Wealth Is Concentrated in The Hands of People Who Can Mobilize (organize) Labor, Thus Creating Inequality.

(Explain why marx as wrong) - As Inequality Gets Worse, the Society Loses Cohesion. the Standard of Living Goes Down for Normal People, While There Are More People Struggling for The Good Jobs than Can Fit

- This Competition for The Few Goods Jobs Results in The Society Splitting Into Different Factions Trying to Push Their Faction to Victory so They Can Succeed.

- These Factions Cause a Civil War, with One Faction Killing Off the Other, Resulting in A New Unified Population. at Some Point a Major Plague or War Happens that Lowers the Population Back to Healthy Levels.

- Repeat

Current Explanations of Causes of Cycles

- Thomas Piketty: Anti-Capitalism: The upward concentration of wealth creates unsustainable inequality, fostering resentment and conflict.

- Peter Turchin: Anti-Managerial-Elite: Overproduction of elites and oversupply of labor lead to destabilizing pressures on society.

- Curt Doolittle: Failure of Suppression of Criminality: Both of these conditions exist because we fail to measure externalities and capital, creating a market for the institutionalization of irreciprocities, which leads to parasitic rents and elite overproduction. In other words ‘a measurement problem’.

It’s Not Ideology It’s Just Science

In other words, our understanding of history, and our position, is not ideological. It’s not an opinion. It’s simple behavioral science. We are demanding a reformation that suppresses the criminality that naturally evolves in every civilization that lacks the institutional ability to suppress criminality because of an absence of awareness of the criminality, a justification of that criminality by the criminal elites, and a failure to develop a system of measurement sufficient for the incremental suppression of that criminality such that the overproduction of systemic criminality is impossible. And as such the only vehicle available to elite aspirants is scientific, economic, political, aesthetic or to depart to foreign lands (as did england).

Previous eras lacked a measurement necessary to resolve their differences so they resorted to fictionalisms: idealism, whether economic, political, social, or theological.

We are providing that system of measurement. It’s a revolution in ‘consciousness’. It looks like english and ideas, but it’s not. It’s a system of measurement of sovereignty, reciprocity, truth, and duty necessary for the incremental suppression of criminality across the spectrum.

Not that crime is an opinion any longer, but a fact. Not that any criminal is willing to give up his crimes. Not that organized crime in the academy, education, state, media and finance, and by extension some of industry, will not resist it. And given the legislature, because of incentives, is a participant in and facilitatory of organized crime, and the courts lack the law as a system of measurement to correct it … what means of correction of criminality remains for us?

Prediction of American Cycles of Conflict

-

The Three Cycles that Predict Civil War in America

1.Strauss-Howe:This Follows Generational Patterns, in Which America Has Had a Crisis Every 80 Years Due to This. in The 90’s They Predicted the 2020s Would Have a Civil War in America.

2.Turchin-Hackett—fischer: societies Experience Periodic Collapses Every 250 Years or So, Which Thus Result in Revolutions, Plagues and Wars. Hackett Fischer in The 80’s Predicted a Crisis Like This Around 2020 While Turchin Made a Computer Model in 2010 that Predicted the Same Thing.

3.Amaury-Fahry-Spengler: civilizations Go Through Life Cycles that Last Several Thousand Years with Really Stark Similarities. the Comparison Between Western and Classical Civilization Are Especially Strong, with The Us Positioned in The Same Position as Rome in 100 Bc Before Its Civil War.

Key Principle: Reciprocity and Proportionality

- Revolutions and civil wars begin when there is a perception of persisting cooperation but an experience of irreciprocity and disproportionality. As soon as elites or ascendant classes stop reciprocating the benefits of cooperation, defection begins, leading to resistance, conflict, and potentially civil war.

- In other words, order produces positive markets for cooperative productivity and negative markets for cooperative criminality

- These markets evolve in complexity.

- The common law lags, legislative law lags, authoritarian law reacts. All are risks. But common law is better at the incremental suppression in teh absence of corruption because it is purely empirical – but it needs a system of measurement.

- The discovery of irreciprocity in courts of law is the only means of incremental suppression of innovations in criminality limiting us to incremental expansion of innovations in cooperation while at the same time evading legislative and authoritative dicates and their openings for corruption and manipulation.

- The challenge: the adoption curve vs the demographic composition combined with its store of human capital and institutions producing that human behavioral capital. In other words, responsibility and its exercise are dependent upon the rate of adaptation of the population given the people capable of not only understanding, but behaving and enforcing that rate of adaptation – the incremental suppression.

Criminality by Failure of Due Diligence

There are only two forms of criminality: Criminality is a distinction of behavior within a civil order (polity). A) Positiva: Misbehavior across the spectrum, B) Negativa: Failure to Identify and Suppress criminality. In other words tort (tresspass) does not depend on your intention but on your failure of due diligence.

This observation of the failure of ‘duty’ to exchange of sovereignty, by the exchange of the duty to reciprocity, heroism, truth, excellence, and beauty (meaning no cutting corners.)

That duty requires the ability and the will to bear the responsibility of that duty in exchange for ‘citizenship’ meaning ‘voice’ in the exercise of responsibility for the polity and all in it whether personal, private, semi-private, or common.

This example reiterates the difference between the western tradition and the modern tradition, and the broader world tradition: the west requires responsibility across the spectrum and one is guilty of a failure of due diligence whether in producing a crime or suppressing it. This is the reason we have the luxury of folly: prosperity and trust. And that trust is a weakness because we are too easily swayed into a failure of due diligence.

This is what we are restoring to our law as a means of ending the sale distribution and production of irresponsibility.

(Close with Brad’s Example of the Ditch – “Don’t Pay Back Pay Forward” as the example of a high trust society’s institutionalization of responsibility. It’s a higher order of contribution to common behavioral capital than simple honest and reciprocal exchange: it’s HEROISM.).

(Have brad explain the ‘ditch’ is the salt river, and 1/2 mile deep) 😉

(END THIS TOPIC)

SCRAP

- How We Got Here